Break A Leg, Jim Crow

African American Show Business

and Challenges to Segregation, 1897-1914

Introduction

While much of the scholarship of the early Jim Crow era has rightly been focused on the political and economic resistance to Jim Crow by blacks at the turn of the century, this analysis focuses on the sometimes-ignored aspect of popular culture. Specifically, this paper explores the dynamics of the African American theatre circuit and the varied experiences not just among black audience members but also performers, theatre managers, and the black press. I argue that the black entertainment industry was a unique battleground to resist Jim Crow. On one level, theatre acts were highly popular among urban blacks and their potential economic strength could effectively persuade theatre owners to rethink Jim Crow policies. Similarly, black entertainment proved popular to whites as well, with some acts being sold to mega white Broadway theater owners like Florenz Ziegfeld.

However, even with attractive shows to white audiences and their economic might, blacks could not rid Jim Crow out entirely. Some theaters in the urban north later returned to segregated theaters policies while white financers pulled out of funding theaters with black acts. Still, the black theater scene that arose at the turn of the century spawned early entrepreneurship in Harlem and other major urban centers. Black performers were no longer only subjected to traveling minor acts but could also become mainstream performers at reputable large playhouses. While still fighting Jim Crow policies at these playhouses, blacks negotiated segregation with a proliferation of a distinct African American culture. This culture encouraged blacks to patronize black businesses and allowed for expression beyond the constraints of what constituted acceptable material for black entertainers (race humor, all black casts of Shakespeare etc.) Similarly, with major help from widely circulated publications, the black press critiqued the projected self image of their race in entertainment in an effort to fight off entrenched stereotypes of African Americans as immoral, hyper sexualized, and diseased.

The Rise of African American Vaudeville

It may be easiest to begin with African American culture that was largely inaccessible to non-elite blacks at the turn of the 20th century. In his monograph on the black aristocracy of the period, historian William B. Gatewood only minimally discussed the cultural preferences of the black upper class. In Washington D.C., a group of upper class African Americans formed the Treble Clef Club in 1897, aimed at educating themselves in the study of classical music. Though at first glance, it may seem like the black aristocracy was yet again embracing an integrationist strategy to disassociate themselves from the uneducated members of their own black race, it is important to note that the club members were greatly interested in black classical musicians, particularly Afro-British Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. After visiting with the accomplished black British composer in London, one African American aristocrat pondered creating a separate choral group to sing exclusively the works of Coleridge-Taylor. The members of this newfound group yearned "to develop a wider interest in the masterpiece of the great composers and especially to diffuse among the masses a higher musical culture and appreciation for the works that tend to refine and cultivate."1

The Marines "had no stomach for 'a nigger show'"

To members of the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society, classical music served as a tool for refining black identity and combatting stereotypes of African Americans as universally poor, diseased, and immoral. Black classical musicians and their African American elite followers attained more respect from whites at the turn of the century, though this did not by any means mean they were free from discriminatory practices. In 1904, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor performed at two New York concerts attended by thousands of wealthy patrons, including military officers, members of the presidential Cabinet, and "probably a thousand other white lovers of music," the Clifton Springs Press reported. While Samuel Colerdige-Taylor was universally praised for his performances, the local press lamented the "orchestral deficiencies and bad execution" of the United States Marine Band, who were "under duress" to perform. Several members of the Marine Band "privately announced that they had no stomach for ‘a nigger show.'" To the Clifton Springs Press, the Marine Band's assertion was ludicrous. After all, the fact that whites dressed up in their fine immaculate attire to listen to a black musician "would have thrown [Uncle Tom] into fits.2

Needless to say, by the turn of the century, most Americans, white or black, were not regular patrons to high-class entertainment like classical music concerts. The most popular entertainment for lower to middle class Americans at the turn of the century was vaudeville, a form of theater largely credited to have been developed by Italian immigrant New York theater owner Tony Pastor.3 Vaudeville theater included diverse, unrelated acts, including singing, dancing, magic, circus performances etc. In the late nineteenth century, the vaudeville theater was often associated with a working class clientele and attributed to bringing immorality and vice into the American entertainment industry. In San Francisco, home to Pastor's first theater, vaudeville was often considered a vice, especially since the lower class men attending the shows partook in other pleasures like prostitution and drinking, both highly targeted in the heyday of the progressive movement. Pastor made by the vaudeville theater respectable and dignified to the middle class in two ways. First, he eventually eliminated alcohol from his theater. Secondly, in an effort to make the stage more family friendly, he welcomed women into the theater; after all, "the primary distinguishing mark of the 'refined' vaudeville was not the show on stage but the women in the audience. A mixed audience was by definition as respectable one, a male-only one, indecent."4

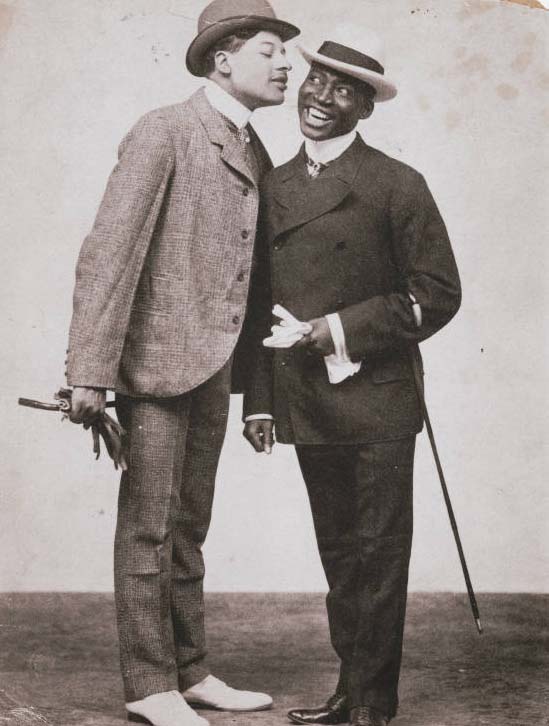

Despites vaudeville's potential for providing "something for everyone," the new form of entertainment copied the early popular minstrelsy's incessant negative depictions of African Americans, another way for white Americans to control the representation of a supposedly inferior race. 5 According to historian Camille F. Forbes, "blacks were more likely fodder for vaudeville performance than a desired audience for its shows." Even with the introduction of blacks into the vaudeville circuit, whites demanded black performers to perform as their understanding of blackness. That is, the only "authentic" portrayals of blacks were the ones commonly performed by whites in black face acting like buffoons. In order to break into this highly competitive vaudeville market, George William Walker and Bert Williams did just this, using the exact language and mannerisms of black-faced white entertainers.6

This is not to suggest, however, that black entertainers lacked agency entirely in early vaudeville. Forbes insisted that Walker and Williams subtly pushed back against negative depictions of African Americans. She claimed that their singing of the song "Two Real Coons" was revealing to the audiences, ironically challenging them to reconsider the need for black performers to wear black face. Still, Walker and Williams had the look and played the part, still using the disparaging word "coon" and still wearing burnt cork. Minstrel's "darky humor" had yet to fade even with this new and exciting form of amusement.7

Though the working and middle class black community largely embraced vaudeville entertainment like their white counterparts, it is important to not forget that resistance against Jim Crow in high culture was not lost on the larger African American community. Despite the prohibition of many non-elite African Americans to attend operas or orchestra concerts, especially in the Deep South, the ability for black performers to break through these segregated performances often caught the attention of the black press. In February 1912, the New York Age's Austin reporter joyously declared "the bars of discrimination were let down in [Austin]" after Emile Nelson appeared in a performance at a Texas opera house with an all white cast. The reporter claimed that this was the first time in Austin's history that a black person had a speaking role in an otherwise white show. When the cast of the operatic show, "Over Night," first got word it was to tour in the Deep South, Nelson offered to resign in an effort to avoid confrontation with racist white southerners. The production manager refused to change the show. According to the report, after three months of stage productions in the south, "Over Night" had yet to bring about even one denunciation or protest. In fact, Atlanta's white newspaper the Constitution praised Nelson while Houston's Post assumed that impressive makeup contributed to Nelson's dark features, apparently unaware that the character was not a white actor.8

Interestingly, the Austin reporter believed that Emile Nelson's apparent groundbreaking appearance in the south probably would not have been of interest to New York readers, especially since Nelson was not a well-known actor. But Nelson's presence in the Austin production is indubitably notable, especially "after taking into consideration the temperament of the majority of white in the South on the race question, that Father Time has wrought a change for good in the southern states when a colored actor can appear nightly for three months with a white show in the leading playhouse of the southern state without occasioning adverse comment or undue excitement." The New York Age reporter viewed the right for a place on the stage as a milestone in the fight for fighting for Jim Crow and acknowledged that how the apolitical nature of black show business allowed for African Americans to, mostly unbeknownst to whites, resist Jim Crow at his most defended corridor.9

The Black Theater and the Jim Crow Paradox

As commendable as breaking down barriers in high art venues like opera houses in the battle against racism and segregation was, since the majority of African Americans had greater access to vaudeville entertainment at the turn of the century makes the ostensibly populist amusement one of slightly more importance. After all, by 1910, nearly every black community in the south had at least one small vaudeville theater, "nothing more than black commercial entertainment for black audience"; a decade later, African Americans owned and managed roughly one hundred of the nearly three hundred nationwide theaters that accepted black clientele.10 One such venue was the Washington D.C.'s Howard Theatre, which opened in 1910, named for its closeness to now one the nation's leading historically black colleges, Howard University. While the Howard Theatre appeared open to the all classes of the African American community in the District of Columbia, class divisions were clearly visible, with orchestra seats and boxes reserved for the "black bourgeoisie . . . [the ladies] dressed in gowns fit for goddesses." While not entertaining the masses with song, dance, or comedy shows, the Howard also served as a community gathering spot for Washington's black community.

It should be stressed how interconnected the black owned theaters of America's urban centers really were by 1914. New York's Lafayette Theater often traded shows and productions with the Howard. Black entertainers from around the country found success at black owned venues even outside the east coast, including in St. Louis (the Booker T. Washington Theater), Philadelphia (the New Standard and Dunbar Theaters), and Chicago (the Pekin), largely considered the first city in the nation, much less the Midwest, to host a black owned theater of merit.

These black owned theaters were life saving venues for black entertainers after 1910. According to census data, there were nearly six thousand African American actors, actresses, and musicians in the 1910 that found success not only in America's theaters (sometimes even integrated ones) but on worldwide tours as well. But beginning in 1910, according to historian James W. Johnson, black entertainers faced expulsion from most theater companies in the city, mainly in New York's famed Broadway district. These African Americans began performing at exclusively black theaters in Harlem. This is revealing, since unlike the performers of existing small black theaters like in the south or in Chicago, African American New York entertainers had began and sustained their careers mostly in front of white-only audiences.

The expulsion, a result of racist voluntary enactment of Jim Crow policies in New York's public accommodations, led to a distinct African American culture, a time "when polite comedy and high-tension melodrama gave way to black-face farce hilarious musical comedy, and bills of specialties … a Negro audience seems never to laugh heartier than when laughing at itself --- provided it is a strictly Negro audience." Not all black entertainers, however, were in popular vaudeville acts, the preferred choice for the majority of African American theatergoers. Since many often previously performed in front of all white audiences, the training of black entertainers was diverse, from vaudeville to Shakespeare. Intense, dramatic, and white shows performed by and for black audiences at New York's Lafayette or Lincoln theaters were highly controversial. The black elite condemned black productions of dramas and white-written Broadway plays that they saw had little connection or meaning to the lives of ordinary African Americans. Still, historian Jervis Anderson described how such segregated markets allowed black performers "the only chance they had of appearing on the legitimate stage, and they enabled Harlem audiences to see black actors and actresses in something other than the usual song-and-dance routines." Similarly, these dramatic actors could investigate material and plot lines once though unheard of for black performers in front of white audiences, including the taboo of "romantic love-making." After 1910, the segregated Harlem theaters, though established because of racist Jim Crow, allowed the Lafayette Players and other black stage entertainers "for the first time [to feel] free to do on stage whatever they were able to do."

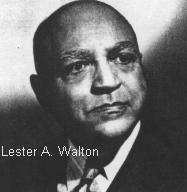

Segregated black productions and theaters were not just of benefit to black performers. Just as the DC's Howard Theatre became a de facto African American community-gathering center, many viewed the African American theater as, in the words of historian Jacqui Malone, a "secular temple for black communities." Responding to the arrival of two African American touring shows in New York in May 1912, New York Age theater critic Lester Walton enthusiastically explained that "colored shows are . . . regarded by us in the same class with strawberries, flowers, and straw hats for men—things that bloom in the spring tra la la." Perhaps Walton is a bit biased here; after all, as the head entertainment credit for the New York Age, he was expected to show more than usual excitement for black touring entertainment stopping through New York. However, he illuminated how many middleclass, and perhaps even working class, African Americans felt about touring productions of black entertainment. Less than two years after the exile of black entertainers on Broadway, the brief one-week stay of two fresh traveling productions was of great importance. Walton's only sadness of the whole affair appeared to be the unfortunate timing of the productions. Their one-week engagements overlapped on the same week in May, overloading African American excitement over these shows into a short period of time. Still, those like Walton "who relish colored musical productions are thankful for what they can get, and are taking advantage of the golden opportunities presented by seeing both shows in one week."

These experiences by African American entertainers or audience members during the Jim Crow era are not to excuse the horrific and deeply unjust racist policies at the turn of the twentieth century. It does, however, complicate traditional notions of black oppression by presenting brief episodes of agency and resistance to an otherwise solidified white supremacist order. No group benefitted more after the segregation of theaters in the 1910s than African American theater owners, who now had a seemingly reliable base of customers with limited competition, at least from whites. In her recent work on black entrepreneurship in relation to black funeral homes, historian Suzanne Smith discussed the importance of the black economic market to black businesses, similar to this analysis of black owned theaters in Harlem. Smith also tied in W. E. B. Dubois's "group economy" message and Booker T. Washington's 1895 Atlanta speech in her argument about the "paradox of early black capitalism." In her view, "black entrepreneurs tried to use their businesses as a form of self-help and racial uplift and—at the same time—as a strategy for fighting racial prejudice and discrimination." These two goals, however, were not always compatible; African American theater owners thrived on a segregated market and, at least theoretically, calls to the end segregation would go against their own economic self-interests.

This is most evident in the African American press' constant discussion of struggling theatres in first decade of the twentieth century. In April 1908, the New York Age's Lester Walton reported that a new black theater appeared to be set to open in New Orleans and promised to be "the finest Negro theatre in America." Yet, in the next paragraph, Walton lamented the near closing of the black-owned Dunbar Theatre in Columbus, Ohio. "It is highly probable [the Dunbar will close]," Walton warned, "if the Negroes of Columbus don't patronize the pretty little theatre much better than they have been doing of late." Walton appealed for African Americans to support the Dunbar Theatre simply because it was one of their own, owned, operated, and presented solely to African Americans. After all, there was little excuse for the black Columbus community to let the business shut down. According to Walton, ninety percent of Columbus' black population consisted of theatergoers. "It would be noting to their credit to allow the Dunbar Theatre to close because of lack race patronage. . . Chicago, New Orleans, Montgomery and a few other cities are supporting Negro theatres, why not Columbus?" Similarly, just a month after reporting on the Dunbar, the Age reported the likely closing of Chicago's Pekin Theatre for the summer months due to "bad business." Pekin, "the model for the establishment of . . . black theaters in other major American cities," after 1905 was unable to keep its doors open year round. Black owned and operated theaters seemed extremely volatile financial investments. Just a month earlier, in the same piece listing the Dunbar Theatre woes, Walton discussed the great success of the Follys of 1908 [sic] and noted that "business is much improved at the popular little South Side theatre . . . everybody is happy." Chicago theatergoers may have been happy to see the show, but the Pekin itself was no thriving economic success.

Resistance, Self-Regulation, and the Black Press

Despite the birth of African American owned theaters across the country and the opportunity to see talented performances at these venues, blacks increasingly yearned to see shows that took place in white owned establishments. Admitting the economic potential of African American patronage, some white theater owners allowed African Americans entrance to their venues, yet forced them to sit in only the worst seats available. This usually meant blacks were restricted to the theatre balcony, or sometimes referred to as the "buzzard roost," the peanut gallery," or the most sickening, "nigger heaven." Black attendance to segregated theaters was highly controversial in the black community. In Atlanta, newspaper columnist E.B. Barco threatened to publically expose the names of African Americans who patroned segregated theaters. "If the Negro women will just stay in their places, it will be an easy matter to control the men," Barco wrote in 1905. "and soon or late we will have an opera house which you can go [to] and not be molested or criticized." Barco's logic is difficult to decipher. His specific targeting of African American women implicates them as the roadblock of racial progress; Because black women attending segregated theaters, they were viewed as subservient to the white Jim Crow system and thus not true ladies. Why men are not of equal importance to Barco's critique is not known.

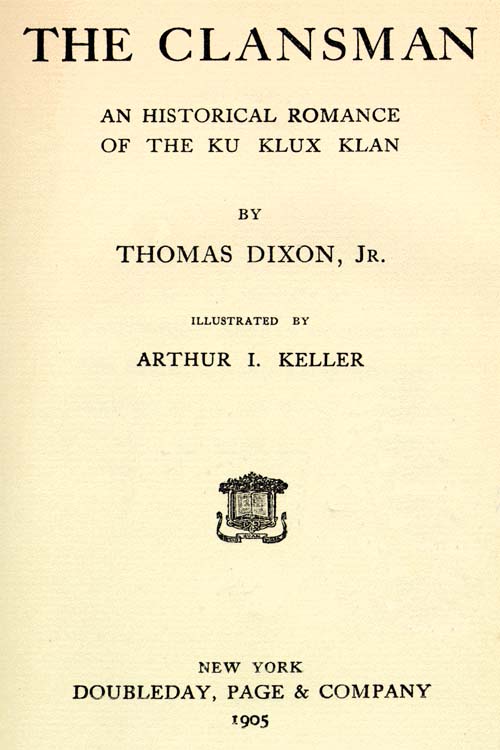

Incredibly, as historian Tera W. Hunter documented, the black citizens of Atlanta who attended segregated theaters were not unresponsive to the racism and oppression around them. When they encountered derogatory representations of their race on the stage, like in Thomas Nixon's play The Clansman, some black patrons audibly laughed at the outrageously racist portrayals, much to the ire of the white audience members in the orchestra section. When confronted by whites, African Americans in the "buzzard roost" booed and hissed and, in a sure sign of guts, threw soda bottles at the white spectators below them. Sadly, Hunter gave us no additional information about these brave Atlanta troublemakers. One has to wonder if they faced any form of harassment for their tactics; men and women in the South were lynched for far less.

Somewhat like Barco, the northern black press fought against segregation and attempted to regulate the ways African Americans depicted their race on the stage, all in an effort to fight damaging stereotypes that whites had inflicted of them since the antebellum era. The black press incessantly targeted segregation at New York theaters like the Grand Opera House, one of the city's largest theaters in 1914. Though the Grand Opera House appeared to be a desegregated venue, upon one visit, Walton noticed that African Americans were only sold tickets for seats after the first six rows or in orchestra seats on the left side of the theater, while whites were seated in the middle, right, and front rows of the theater. The only African Americans who received seats outside this invisible reserved section were blacks who "fooled the ticket seller as to his racial identity." Those African Americans who complained about their seats, especially seats obstructed by building posts, were refused better seats, despite the orchestra not being filled to capacity. Walton noted that segregation of the Grand Opera House appeared a new phenomenon, something he had not seen at the theater a few years before his editorial. He implored the New York African American community to not let New York go the way of the south. "If this wave of prejudice is spreading, it must be checked . . . A principle is involved which is dearer than any financial consideration to all Negroes who want to be regarded as men and women—not cattle."

Before the Lafayette Theatre came under the management of an African American in 1914, even "highly respectable" African Americans were barred access to the theatre's orchestra seating. Included in the "respectable Negros" who could not secure Lafayette orchestra seats were Tammany Hall politician Edward E. Lee and even African American employees of respectable white banks. However, in a potential sign of black economic power, the Lafayette Theatre suffered from dismal orchestra seat attendance and eventually passed management hands. Sadly, little is known or written about the actual black theater owners themselves. Perhaps not surprisingly, one theater owner who is credited for desegregating one of New York's popular theaters was our New York Age friend Lester Walton. Walton took over management of the Lafayette in the 1914, turning the theatre into "the most stylish black showplace in Harlem," and his bookings of mega popular black performances like Darkydom showed "that the colored musical show is once more on the ascendancy."

Also on the ascendancy in the 1914 New York theater scene was burlesque, an art form that largely took the form of mocking Victorian views of decency in regards to dress, sexuality, and language. Scholar Jayna Brown argued that burlesque was always racialized, with black burlesque women often wearing blonde wigs. The women were desired by men because of "particular fantasies of the working woman's body . . . [for their] physical strength and endurance, properties outlawed from middle-class tenets of femininity." It did not help that many whites considered black women who danced, in non-burlesque ways, as sexually immoral and promiscuous. Now, black women who used their bodies in explicitly sexual means clearly lived up to long held white stereotypes of black women as innately licentious. It seemed logical, then, that the black press sought to question African American entertainment that associated itself with the deemed immoral art form. Lafayette manager Walton asked, "Is the colored musical show to be restored to its former healthy condition through burlesque? It looks very much that way." But instead of advocating against African American participation, the New York Age contributor believed that the burlesque of the previous decades was vastly different than 1914's incarnation. "No so long ago," Walton explained," the term ‘burlesque show' was a synonym for a vulgar display of female limbs and a vulgar presentation of the English language." To Walton, burlesque had now become acceptable, since the sexuality and offensive jokes were tamed. In fact, Walton believed that burlesque could greatly contribute to existing black entertainment's popularity. Burlesque can now be appreciated "without hanging his head in shame --at a time when burlesque has reached its high-water mark for decency."

Though Walton's judgment might appear only that the black press was simply highlighting the revived art form in their editorial, the fact that the newspaper had to publish the item and explain the apparent sea change in burlesque content suggests a veiled defense. The black press often subtly tried to combat stereotypes of African Americans as lazy, immoral, and diseased. In October 1914, the Laffayette Theatre booked famed black performer Sissieretta Jones, popularly known as Black Patti, for a historic $500 for a week's worth of shows, the largest amount ever paid, according to the Age, to a performer at a black theater. Since Walton was now the owner of the Lafayette, his name no longer appeared on the Age's editorial page, perhaps to distance himself from any allegations of bias. But the article made specific mention that the Lafayette spared no expense "to secure the cleanest and best colored acts obtainable," language defining African American entertainment as wholesome and respectable. The black press also aimed to regulate the specific behaviors of African Americans in an effort to fight off racial stereotypes. Two years prior to taking over the Lafayette, Walton wrote of his anger that patrons, presumably black as they were coming out of a Harlem theater, left their in middle of live vaudeville acts. "They made such a rumpus," Walton nagged, "that the performers themselves hardly knew what they were saying, and those in the audience knew less." If he had it his way, and ironically enough, in two years he will, Walton insisted on instituting a ban on leaving ones seat until the end of each act. The author led his lengthy entertainment column not with other mainstream news of the day, like a boxing match, desegregation in playhouses, or baseball recaps (back when baseball actually mattered… sorry Nats), but with a note on etiquette. It very well may be that Walton was genuinely annoyed and distracted because of rude patrons at the Harlem Theater. But there is also a sense that he is trying to reform the personal decorum of certain blacks. In a world where the behavior of a single African American could taint the reputation of the entire race, perhaps Walton considered that his article might serve help to avoid any future stigma making. For instance, Walton might reject the actions of those brave Atlanta residents and their coke bottles.

Similar calls for improving individual black behavior can be found in a defense of a female back entertainment act. In December 1913, the Griffin Sisters wrote the New York Age to protest their lack of payment from a white theater owner in Rome, Georgia, Charles P. Bailey, who catered to African American clients in Atlanta. The sisters alleged that when they approached him for the payment he promised, Bailey pulled out a gun and threatened, "to shoot the Northern nigger and show what a Southern white man could do." The group added that Bailey's "house does not bear a reputation for a refined, clean vaudeville." The Griffin Sisters asked the Age to warn other black performers not to do business with Bailey in the future.

Yet again, Walton responded and defended the reputation of the Griffin Sisters. Walton contended that Bailey's only goal as a southerner who ran a black theater was to make money off the "illiterate Negro" of the South. He explained that theatres like Bailey's "are seldom frequented by the better class . . . so long as [Bailey's] theatre is crowded it is immaterial who patronizes his house or whether the brand of entertainment given is reined or vulgar. It is the money he wants." But while Walton praised the Griffin sisters for trying to aid to bring apparent wholesome entertainment to the south, Walton urged Atlanta blacks to reject segregated theaters and create a black-run theater of their own. Three months later, the Age published the response from Bailey, whom denied the Griffin Sisters' allegations. Walton refuted Bailey's letter but noted that the fact a white manger sent a letter in the first place is "an indication that in the South there are many white people who much prefer to be thought well of by colored people than otherwise."

The Griffin Sisters-Bailey confrontation is revealing on two fronts. First, the New York Age's action in defending the Griffin Sisters was another sign of the black press's aid in regulating and enhancing the black entertainment industry. The newspaper pushed again for wholesome entertainment and in doing so attempted to align the black community on the side of morality instead of vice and greed (like Bailey). The press also encouraged the construction of yet another black-owned theater in the South. Instead of pushing for greater attendance at segregated accommodations, the Age supported this separate, distinct black entrepreneurialism. It seemed that the link between entertainment and political activism could be quite thin. Second, like Walton noted, the fact that Bailey felt the need to respond to allegations of intolerance in a northern press suggest his economic success as a white owner of a black theater was at risk. If the Griffin Sisters were to be believed, even racist whites depended on black consumer power.

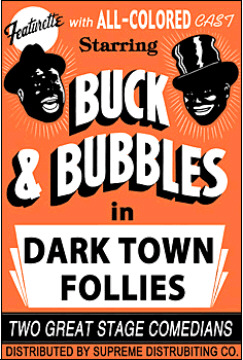

In a final example of elements of resistance regarding the black theater in this period, it would be hard to omit the importance of the Darktown Follies. In a rebuke to earlier black aristocrats who complained of African Americans not creating their own shows, J. Leubrie Hill composed and lyricized an entire romantic comedy that broke several cultural theater taboos, such as onstage black intimacy. The showed opened at the Lafayette in 1913, originally planned for a one-week run but extended for an entire season and then a tour of other playhouses.

Florenz Ziegfeld, a Broadway director and producer of the annual popular Follies productions, visited the Lafayette in 1913 to watch a performance of the Darktown Follies, a show only slowly gaining a reputation outside the black community. As the master of the Broadway stage, Ziegfeld was shocked at the caliber of the black Darktown Follies performances and purchased a number of acts from the production to be used in his own show. Instead of hiring the same black actors and actresses to repeat their performances on the Broadway stage, Ziegfeld instead hired black performers to teach the choreography to white entertainers who would replace them once the show made it to Broadway. Despite this limitation, upon the original Darktown Follies's cast return to the Lafayette Theater in June 1914, the black community constantly sold out tickets to the show, a run that would not end until two years later. Even though Ziegfeld had incorporated some of the best aspects of Darktown, one of the famed Broadway producer's white stage manager explained that, "the trouble is . . . you have a mighty hard time getting white performers who can ‘ball the Jack' and do the ‘Eagle Rock' as effectively as the colored performers." Though Ziegfeld refused to hire full casts of a popular African American show, without the African American casts, he was unable to exactly replicate the magic he saw when he first viewed the Darktown Follies. Interestingly enough, the Darktown Follies, the success of Hill, his cast, the choreographers, and finally the delight of the black audience who frequented the Lafayette for the three year run of the show, was all a result of the purge of black performers from white theaters in 1910. This exile led to the creation of a new role for African American entertainers and allowed them to push the boundaries of acceptable content on stage for blacks.

There were black entertainers who were considered talented enough to gain admission back into or sustain their place in white shows, including the Ziegfeld Follies. Ziegfeld hired Bert Williams in 1910, one moment of mixed-race casting among the white Follies cast. Author and Ziegfeld biographer Ethan Mordden wants his readers to think of Ziegfeld as progressive because of this action, which is just nonsense; one black hire, especially a performer that can be hidden behind all of enormous costumes of the Follies girls, does not mark the Broadway king a racially progressive man. Furthermore, Williams signed a contract forbidding him from being on stage at the same time as any Follies girls, in part, to secure his own protection in the event of a tour of the show in the less sympathetic south. Still, Mordden is correct in to suggest that Ziegfeld inadvertently challenged gender norms. "Whether or not the audience could see Williams on stage with white women, Williams was sharing a theatre's backstage with white women." In a society that constantly lynched black men for their apparent and more often than not fictitious indulging of sexual relations with white women, the fact that Bert Williams remained in such proximity to scantly clad Follies girls revealed the sometimes amazing reaches and leniency show business had in bending the social order.

Conclusion

This analysis is by no means an exhaustive account of the political forces at work in the African American entertainment industry at the turn of the twentieth century. This paper did, however, investigate Jim Crow in an uncomfortably short and unsatisfying setting. By the 1920s, rising costs of touring and the widespread popularity of the film industry largely cutoff the gains of the African American stage productions. By the onset of the Great Depression, theater booking had all but completely evaporated. Theaters that the New York Age once celebratory announced were desegregated reversed course; blacks again entered theaters from different doors, walked through different hallways, and sat in the nosebleeds of "buzzard roost." Perhaps an enduring historical lesson of the era of American apartheid is that history has never been a linear path of progress. Gains made in one year can be lost in the next, especially in this case, when the forces of white supremacy and patriarchy were sometimes too powerful to challenge. Student of history would do well to reconsider African American performers, journalists, entrepreneurs, and the theatergoing public's complicated but important role in the fight against Jim Crow. Even in entertainment, a realm of our society often thought of as apolitical, African Americans at the turn of the 20th century demanded change—sometimes on the stage, sometimes behind the curtain, but always in the spotlight of their country.

1. William B. Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880-1920 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas ↩

2. "Washington Letter," The Clifton Springs Press, November 24, 1904, page number unknown ↩

3. Camille F. Forbes, Introducing Bert Williams: Burnt Cork, Broadway, and the Story of America’s First Black Star (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2008), 53. ↩

4. Forbes, Introducing Bert Williams, 54. ↩

5. Forbes, Introducing Bert Williams, 54. ↩

6. Forbes, Introducing Bert Williams, 59. ↩

7. Forbes, Introducing Bert Williams, 59. ↩

8. Lester A. Walton, "Music and the Stage: Theatrical Comment," New York Age. The date and page number of this specific article is not included in the digitized version of this page. Due to context clues like advertisements and content information, the author believes it to be dated sometime in February 1912. ↩

9. Lester A. Walton, “Music and the Stage: Theatrical Comment,” New York Age. (see additional note in repeat footnote above) ↩

10. Jason L. Ellerbee, "African American Theaters in Georgia: Preserving an Entertainment Legacy," (master’s thesis, University of Georgia, 2000), 13. ↩