Boogie

Revolution

Inside America's Disco Scene in the Late 1970s

Introduction

Among the sometimes-unnecessary lyrics of disc jockey Don Ray's 1978 disco hit is a plea for listeners to find "more loving," something that, at the time of the record's release, seemed the genre of disco needed little of help actually doing. By the later 1970s, disco, an infectious, often lyricless, four-on-the-floor beat, synthesized style of music, became a national fascination. Some reports indicated that, at the peak of the disco craze, more than two hundred radio stations played exclusively disco music for the entirety of their programming. If they wanted more of a fuller sound than what came out of their transistor radios, Americans could stand in line at more than 20,000 discotheques around the nation. Despite this huge success, disco music's popularity began to wane by 1979, largely credited to rock-n-rollers' hatred of the thumpa thumpa nature of the genre and, to some scholars, underlying American racism and homophobia geared toward the disco artists and fans.

Until recently, disco music and American 1970s dance culture has received little historical attention, certainly nothing to the extent of other twentieth century genres like jazz or funk. Not all of this can be attributed to historical, willful ignorance. For one thing, the disco peak lasted but a few years and, at least in our collective historical imagination, occurred relatively recently, perhaps still too ripe for historians and other scholars to comfortably begin dissecting the fad. However, historians have already begun to tackle other aspects of society and culture during the American 1970s. Moreover, previous feminist and cultural scholars have been fascinated with the MTV generation and the sexual politics of 1980s pop icons like Madonna and Michael Jackson. If extensive inquires can be made into eighties pop culture, the absence of disco scholarship certainly feels odd.

Gay Men and 1970s Nightlife: Washington D.C.'s The Pier

For gay men, disco and disco clubs represented liberation in the post Stonewall era. Gay men of the New York's Gay Liberation Front (GLF) organized dances in an effort to support a new ideology of sexual freedom and anti-capitalism, which explains their distancing themselves from bars like Stonewall. But this distancing from seemingly neoliberal sites did not last long; eventually "bathhouses and discos, rather than meeting halls or community centers became . . . the sensational glue" of the gay community. Gay men's appeal to disco was the genre's connection to escapism. Used to being subjugated as sexual deviants by their families or harassed by police at bars, like at Stonewall, gay men used the unceasing beats and drugs like LSD or poppers in an effort to achieve "dance orgasms." On the dance floor, at least, one could be in a "timeless, mindless state," away from the cruel, homophobic society just outside the club's doors.

On the dance floor, one could be in "a timeless, mindless state" . . .

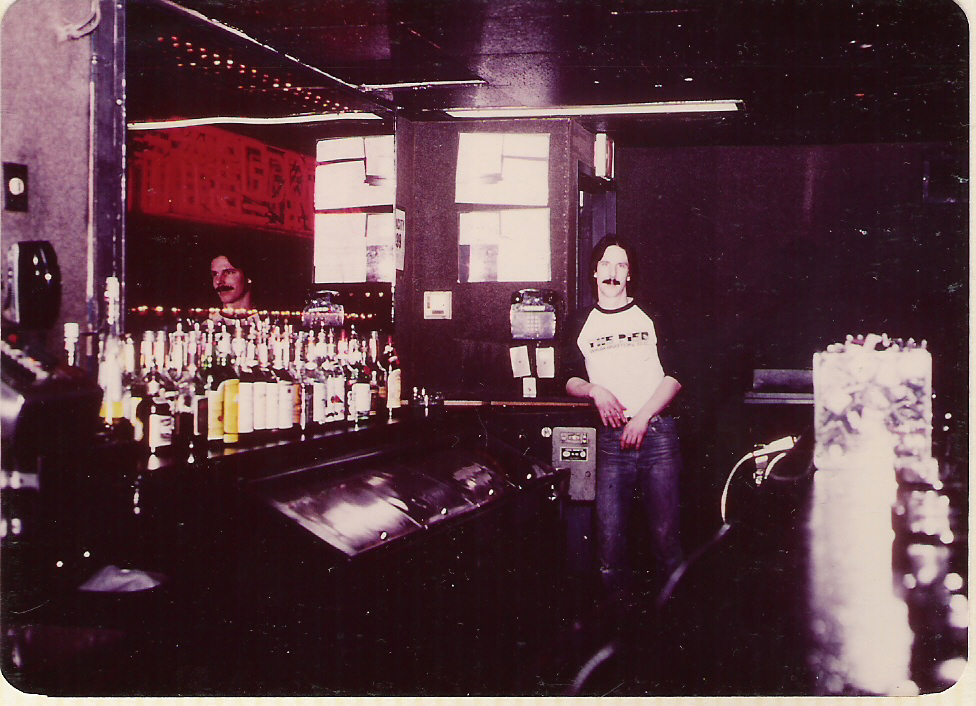

This photo is of the bar the Pier, one of the first gay clubs in Washington DC which opened in 1970. It was known for innovative technology, including telephones at tables, which allowed patrons to communicate with others sitting at different tables. This helped gay men get around local ordinances that banned standing or moving with a drink.

The Rainbow History Project digitized the original photograph. Using basic skills learned in class, I made some minimal touch ups. I still am not totally satisfied with the brightness of the photo. I considered the possibility of putting the picture in black and white, but I feel the color is a nice touch, especially since most images of nightlife are not in color.

Before

After

Beyond Escapism and The Back Door Pub

Escapism did not necessarily mean these gay men exhibited progressive ideals. Popular exclusionary policies included steep entrance fees and the creation of private clubs to keep undesirables out, mainly black, Latino or female patrons. According to historian Alice Echols, disco scholars conspicuously overlook gay exclusionism in an effort to combat stereotypes of the disco clubs as sites only for elites, like Studio 54. Rather, these scholars, like historian Tim Lawrence emphasized underground disco clubs in order to dispel elitist notions. Echols found this problematic; underground clubs could often be closed off just like more mainstream discotheques. Lawrence and other scholars ignored "the subcultural capital, a term Echols borrowed from cultural sociologist Sarah Thornton. That is, missing from previous disco scholars' obsession with the underground disco clubs are the clubs' need to have "the 'right' look, lingo, moves, attitude, and all-important taste that underwrites an underground, and dismisses mainstream audiences as homogenous, conformist, and politically quiescent, even conservative."

What set Echols's analysis on gay men's relationship to disco apart from other scholars is her ability to tie disco to the formulation of new identity, gay masculinity or "gay macho." Echols argued that some gay men's embrace of a new image, resembling a manly, mustached, butch lumberjack, was a result of the disco artists like the Village People. To achieve these ideal, gay men sought to redefine their own images, often literally, by working out and achieving buff bodies. After all, unlike the days in the closet where the gay men apparently desired heterosexual men, they now could romantically and sexually pursue each other. They there no longer "hunters after the same prey." Rather, "we're the men we've been looking for," as some gay men saw it.

My choice for a matte engraving was limited since most of my research is on later 20th century history. I isolated this picture from an advertisement by the Back Door Pub, once located at 1104 8th St. SE Washington, D.C. The Rainbow History Project digitized the original image.

Bad Girls: Disco Feminism

The gay rights movement has not been the sole social historical focus of disco scholarship. Feminist scholars and historians have sought to explain the fad's prominence in relation to the heyday of second wave women's liberation in the United States. In some ways, disco's connection to women appeared obvious. Unlike rock n roll, some of disco's most dominant and prolific performers and headliners were women, especially African American “divas" like Gloria Gaynor, Donna Summer, and Diana Ross. Alice Echols acknowledged the split of opinion over how effective disco is at representing women; was [disco] a cultural arm of feminism," Echols asked, “or a part of the backlash against it?"

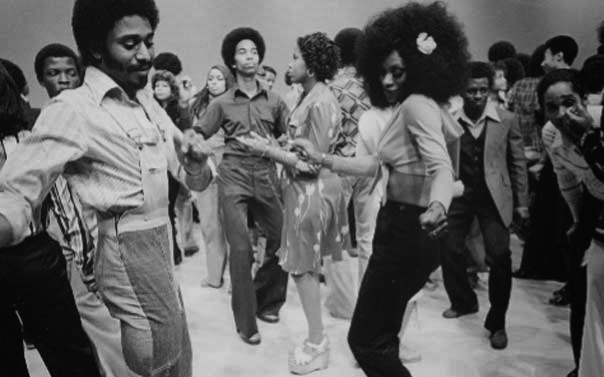

Disco provided elements of female agency. For one, lyrics often spoke directly to women's sexual desires, a taboo topic in other musical genres. Donna Summer's sexual moaning in Love to Love You Baby seemed shockingly inappropriate to audiences who, a decade earlier, were dancing to the sweet sounds of the Supremes' Where Did Our Love Go? Disco culture did not necessarily degrade women as merely sexual objects to be gazed upon by men. Rather, "disco foregrounded female desire to a far greater extent than rock music," allowing female dancers, in clubs where they were not shunned away by gay men or elites, to freely groove without, as seen in films like Saturday Night Fever, a male partner. According to Diana L. Mankowski women could "express their sexuality in public," Mankowski explained, "without necessarily getting a negative 'bad girl' reputation or passively assuming the role of sex object," a stereotype of scantly clad women before the feminist movement in the seventies.

Scholar Julia Kutulas, however, disagrees with this notion of disco feminism. "Disco women were," she suggested, "all surface glitz; they otherwise conveyed little sense of individuality or personality." Kutulas feared that disco divas made feminism and liberation look easy and misplaced, not about the politics of the bedroom or the workplace, but about the right to party and have fun. Even if disco allowed for greater sexual expression for women artists and dancers, women were still were singing songs written by men and under the direction of an industry that forced sexualized images of women. Kutulas chided divas like Summer for their embrace of whiteness in the era of black pride, dubbing Summer a "musical slut" to recorder producing "pimps".

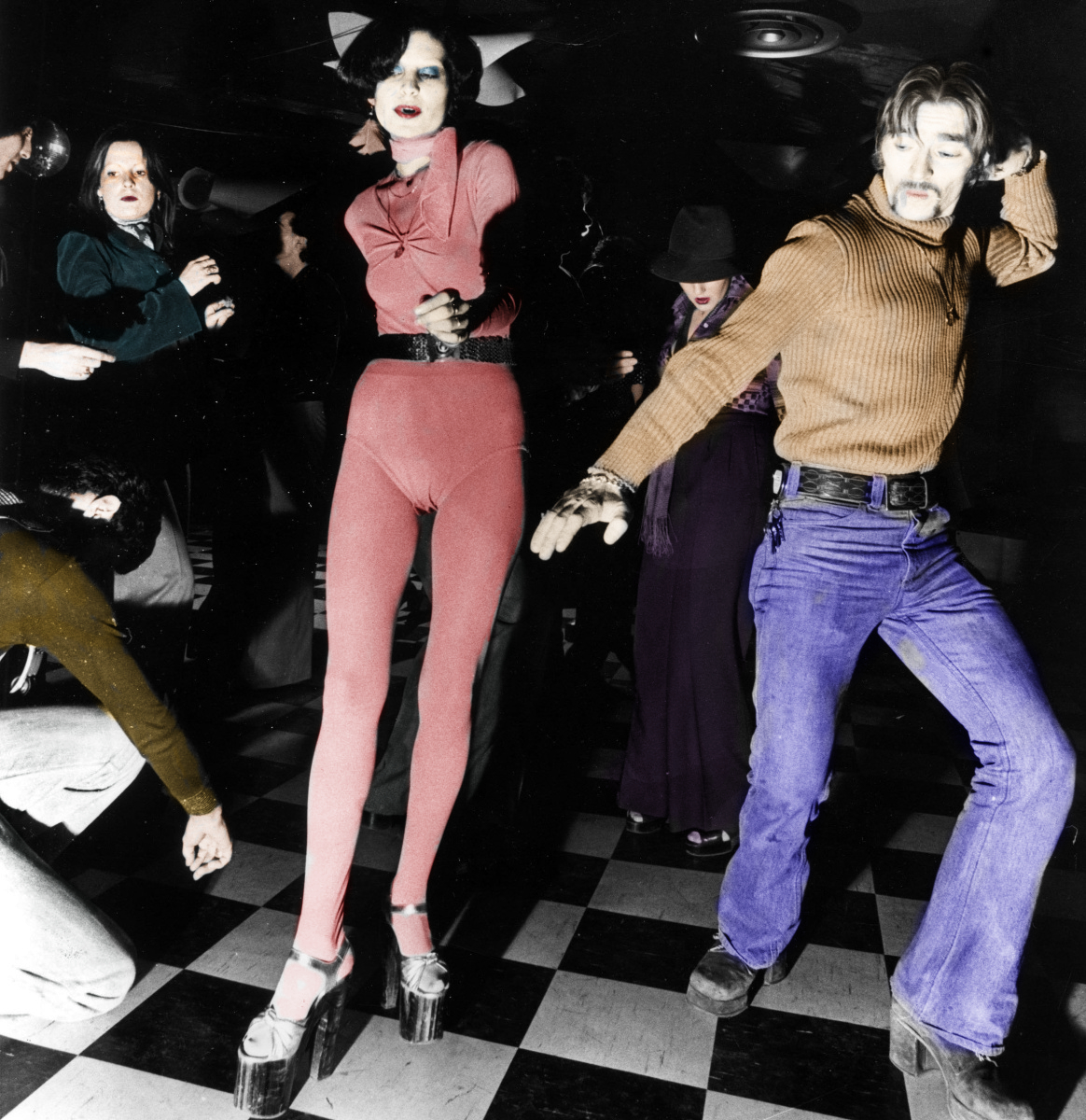

The image of disco dancers to the right was taken at Studio 54 in the late 1970s. My amateur colorization was done using Gimp, an alternative to Photoshop. My life was made easier since the original image was of high quality. It was difficult to get the image to look like it was always in color, mainly since nightlife photographs already tend to look quite dark.

Conclusion

Music needs no defense as a worthy topic of historical inquiry. After all, what would the counterculture be without Joplin or Hendrix or the antebellum south without "Dixie?" Historians continue to prove that elements of our popular culture do not form in a vacuum; they are reflective of the society from which they developed. As our understanding of the American 1970s continues to grow, perhaps we should stop thinking of disco as just a fad. Perhaps it is better to view this pulsing, irresistible rhythmic music as inseparable from feminism, the freedom struggle, economic malaise, gay rights, and a host of other issues that make up the weirdness of the late seventies. The seventies may be over, but as scholars, we certainly haven't had a last dance just yet.